|

Rare words BBC reports may disappear with dying languages: see “In defence of ‘lost’ languages”

|

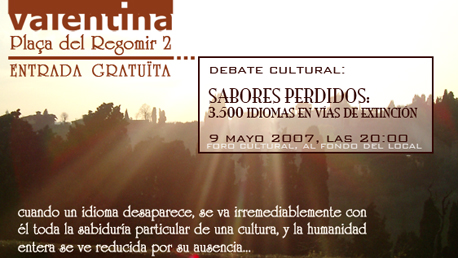

HALF OF ALL KNOWN LANGUAGES MAY DISAPPEAR BY 2100, MORE THAN 3,000 CULTURES LOST

The world’s three most widely-spoken languages, English, Spanish and Mandarin, each enjoy more than 450 million speakers worldwide. These languages are increasingly useful for international business and for diplomacy in an interconnected global society. But languages with fewer than 10 million speakers are now considered “minor” and many long-standing cultures are in danger of disappearing, as only a handful of people remain who can speak them.

In North America, there are now only half the number of indigenous languages spoken as there were 500 years ago, when Europeans began to settle permanently. There are 329 distinct languages spoken in the United States, roughly half indigenous, and yet radical conservatives intent on halting immigration are trying to establish English as the single language in which people are allowed to communicate with their government.

Of the 3 major dialects of Lenape, once spoken widely by pre-colonial tribes throughout modern New Jersey, Delaware, New York and Connecticut, only one remains. It is now spoken almost exclusively on reservations in Oklahoma and Ontario, and is largely forgotten by the two youngest generations descended from the Lenape tribes.

In January 2005, the BBC reported on the withering of the Mati Ke language of aboriginal peoples of Australia’s northern coast along the Timor Sea. Only 3 speakers remain. Two are brother and sister and are forbidden by their tribal custom from speaking to one another after puberty. The third does not live in the area and speaks a different dialect of the language. This means that of the three speakers remaining, their is virtually no common interaction, and no one to pass the language to.

There is an ecology of ideas and linguistics, just as there is ecology in natural systems, and the ecology that favors broad diversity in human language is severely out of balance. Fewer words, fewer languages overall, means a less diverse linguistic fauna for representing the flora and fauna of the natural world and of human experience.

A select minority, only 200 of the 6,800 languages in use today are spoken by more than 1 million people, and the trend is toward less diversity, which means less resiliency in the realm of ideas, less formal elasticity through which to arrive at new or common ideas.

In 2003, Sentido reported that 10% of all languages spoken have fewer than 100 speakers. Such languages are in imminent peril of extinction, and many have no formal written grammar or tradition of textual learning to help them survive even in study.

When these languages fall away before the global influence of the most dominant languages, ideas and perspectives are lost with them. All languages are peppered with or nearly whole-built of words derived from other languages, some prior and ancestral, some parallel and contemporary.

The Endangered Language Initiative (ELI) lists 750 languages that have become extinct or are on the brink of extinction. Of the 154 indigenous languages still spoken in the territory of the United States, 7 are spoken by only one person, another 35 by 10 or fewer. Among these are languages whose cultures were once well known, such as Osage, Wichita and Pawnee.

The BBC report from 2005 also recounts a telling story from the age of European exploration of South America. When the German explorer von Humboldt reached the Orinoco village of Maypures, roughly 200 years ago, “he heard a parrot speaking and asked the villagers what it was saying. None knew since the parrot spoke Atures and was its last native speaker.”

In the United Kingdom, which includes the 3 nations on the island of Great Britain, as well as the territory of Northern Ireland, there has been an effort to revive fading languages like Welsh. The effort in Wales has had important successes, and has become popular among young people, as a sign of identity and as a way of crafting a unique and relevant popular culture.

The Ethnopoetics section of Ubu reports that efforts to digitalize fading langauges are being invigorated, but are racing against time and are steeply challenged by the problem of “new media formats”, meaning both the rapid progression of storage methods and the often frustrating inability of new machines to read devices used for storage only a few years earlier.

For that reason, there is an effort to formulate a platform based on XML, the eXtensible Mark-up Language designed to be compatible with all variants of web-coding, and which should provide a means of recuperating files well into the future. The Open Language Archives Community is helping to study and to define such a platform, in conjunction with projects like E-MELD, in the hopes that future generations will be able to research and even recover lost languages.

According to the E-MELD website for its 1995 conference, the Electronic Metastructure for Endangered Languages Data Project “is a five-year project funded by the National Science Foundation with a dual objective: to aid in the preservation of endangered languages data and documentation and to aid in the development of the infrastructure necessary for effective collaboration among electronic archives.”

But these are pale consolation for those who are losing their families’, their tribes’, their nations’ cultural heritage and who are well aware of the fact that it will pass into extinction when they are no longer able to communicate. Whether by chauvinistic government policies or by cultural seduction or diplomatic convenience, languages used by influential states have historically pushed aside traditional tribal languages.

While historically, English, which is used in a stunning variety of even remote areas, has been charged with “killing” less agile traditional languages, it has also been argued, as by Global Policy Forum, that its ubiquity could help preserve minority languages, by allowing speakers to use English to interact with “powerful neighbors”, not having to cast off their own native languages.

In some areas where minority languages are spoken but are not recognized as official languages of the state, efforts have been made to popularize English usage by factions supporting both the official language and those resisting it in the name of their own local language. This only shows the degree to which history has failed to teach us the most effective method for “saving” a fading language.

It is often the case that the process of extinction is hurried by parents not knowing enough to teach their own children their grandparents’ language. So in 1982, a community aboriginal Maori-speakers founded the Kohanga Reo, or language nests. In a space set aside to function as a community using the traditional Maori language, young children are immersed, surrounded and taught by elderly native speakers and paid teachers.

As the Kohanga Reo “nests” have spread, cultivating what Rebecca Tuhus-Dubrow describes as “a cozy, playful atmosphere”, Maori has seen a fortunate resurgence. Whether the language nest format could be transfered to other languages is not clear, though it would address a common problem, where a language “skips a generation”.

In Catalunya, in northeastern Spain, where fascists once persecuted speakers of the regional language, state schools have been directed increasingly toward instruction in this other of Spain’s four official languages. And Spain, as a nation whose most widely known language, Castilian, is spoken by nearly half a billion people, has written into its 1978 constitution a ban on descriminating on the basis of language usage.

After 40 years of brutal persection and arbitrary detentions, Catalunya’s own romance language is now spoken by more people than Swedish, meaning that, aside from its having to compete with both Castilian (Spanish) and English for young people’s attention, it’s a healthy language, recovered from what was intended to be an imposed extinction.

In the year 2000, Whole Earth magazine went as far as to suggest that 90% of the more than 6,800 languages currently spoken could disappear or become “moribund” by the year 2100. Top linguistic demographers tend to suggest the numbers would be more like 50% going extinct by 2100, if current trends are not reversed.

In 2003, the Independent, a UK newspaper, reported that of the 6,809 “living” languages, 90% had fewer than 100,000 speakers. At the time, some 357 languages were known to have fewer than 50 speakers. Studies showed that the rate of language extinction was already ahead of the extremely rapid rate of animal species extinctions, and accelerating.

- UBU: “Endangered Languages, Endangered Poetries”

- ELI: “How many indigenous American languages are spoken in the United States? By how many speakers?”

- ELI: “750 Extinct and Endangered Languages”

- ELI: “From Threatened Languages to Threatened Lives”

- Common Dreams: “Alarm Raised on World’s Disappearing Languages”

- BBC: “In defence of ‘lost’ languages”

- Open Language Archives Community: “Participating Archives”

- EMELD: “Workshop on Morphosyntactic Annotation and Terminology: Linguistic Ontologies and Data Categories for Language Resources”

- Global Policy Forum: “World’s Languages are Fast Disappearing”

- Whole Earth: “Of the 6,000 languages still on Earth, 90 percent could be gone by 2100″

Pingback: Ziggurat Century: Global Civilization as the New Babel, with Reason for Hope | hotspring.fm